Metz

History and description}}

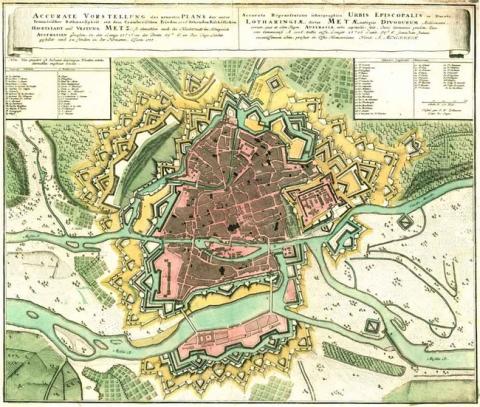

An agglomeration of Celtic origin, Metz became a Roman town named Dividorum, the fortifications of which were constructed under the Late Roman Empire. Ruined by the Huns, it became the capital of the Merovingian kingdom of Austrasia, named Mettis. Becoming an imperial town in the middle Ages, a new urban wall was built from the 9th and 10th centuries, and reinforced in the 14th and 15th centuries. After becoming part of France in 1552, King Henri II tasked engineer Subley de Noyers with the task of modernising the urban wall. It was during this period that the fortress was constructed. The fortress concerned was quadrangular with four bastions, including a Governor’s residence and a food store. It was constructed from 1554 to 1569.

In 1675, Vauban was asked by Colbert to improve the defensive system. He designed a project a year later, aware of the significant strategic interest in the stronghold and delegated the engineer Niquet with the task of implementation. The construction got underway in 1676 but the programme of military construction remained unfinished under Louis XIV, other than the defensive flood barriers of the Seille, a tributary of the Moselle, four kilometres long. The construction consisted of a modernisation of the urban walls and the citadel. All the bastions in the citadel included vaulted low flanks. The counterguard was reconstructed. The ramparts of the Chambière and the citadel were preceded by seven ravelins and hornworks. An additional rampart was constructed on the height of Belle-croix as a gathering space for fifteen thousand men. Water defences had to be added with the excavation of two artificial basins, coffer dams and locks, such as the écluse du pont des Arènes.

It would not be until the Regency and the personal reign of Louis XV that Cormontaigne would complete the urban wall construction, the eastern and northern fronts of which replaced the ramparts of the middle Ages within these areas. The fort de Bellecroix and the fort de la Double-Couronne were constructed in 1731-1733. The barracks of La Chambrière were constructed from 1732 to 1736 and the bastioned redoubt of la Seille was completed in 1737. Cormontaigne worked on the fortifications of Metz between 1728 and 1749, to which he applied his own method of fortification, while remaining loyal to the projects of Vauban and de Niquet. Around the same time, the Bishop of Metz, Henri de Camboul de Costin, had a four-level barracks constructed at the lieu-dit (place name) known as Champ de Seille. In the 1860s, the French civil engineers of the Second Empire started constructing a belt of detached forts around Metz; a modernisation programme which was completed by the German civil engineering programme around 1914. The food store of the fortress had an additional floor built under the German Empire. In the 1930s, some minor modifications were made to this defensive installation.

Current state

The ramparts and the citadel of Metz were demolished from the 1870s to make space for city avenues and a railway station. All that remains is the Fort de Bellecroix to the East, as well as the barracks in the vicinity, and surviving fragments of ramparts to the north, the barracks Chambière, the arsenal, the military hospital, and the military training area with its buildings. As for the citadel, its food store still exists, and has been transformed into a hotel. Two gates dating from the classic period were relocated in the meantime from the boarding school section of a school. The porte des Allemands and the tour Saint-Esprit are what remain of the medieval urban wall. These remains are open to visitors. The relief map constructed in 1825-1826, updated in 1868 (updating suspended following the cession of the town to the Prussians in 1871 and its recapture in 1919) is preserved at the musée des Invalides of Paris but not on show.

Metz

Metz

49° 7' 13" N, 6° 10' 40" E

Type

urban wall, citadel, water defence

Engineers

Sébastien le Prestre de Vauban, Antoine Niquet, Louis de Cormontaigne

Department

Moselle

Region

Grand Est

Bibliography

- MARTIN (P.), La route des fortifications dans l’Est, Paris, 2007.

- WARMOES (I.), Le Musée des Plans-Reliefs, Paris, 1997, p.40.